Class Action Settlement Gives Second Chance to Qualifying US Employers for H-1B Petition Approval

A recent class action settlement is expected to result in U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) approving more market...

Foreign workers fill a critical need in the U.S. labor market—particularly in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) fields. Every year, U.S. employers seeking highly skilled foreign professionals submit their petitions for the pool of H-1B visa numbers for which U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) controls the allocation. With a low statutory limit of visa numbers available, demand for H-1B visa numbers has outstripped the supply in recent years, and the cap has been reached quickly. Research shows that H-1B workers complement U.S. workers, fill employment gaps in many STEM occupations, and expand job opportunities for all.

This fact sheet provides an overview of the H-1B visa category and petition process, addresses the myths perpetuated about the H-1B visa category, and highlights the key contributions H-1B workers make to the U.S. economy.

The H-1B is a temporary (nonimmigrant) visa category that allows employers to petition for highly educated foreign professionals to work in “specialty occupations” that require at least a bachelor’s degree or the equivalent. Jobs in fields such as mathematics, engineering, technology, and medical sciences often qualify. Typically, the initial duration of an H-1B visa classification is three years, which may be extended for a maximum of six years.

Before the employer can file a petition with USCIS, the employer must take steps to ensure that hiring the foreign worker will not harm U.S. workers.

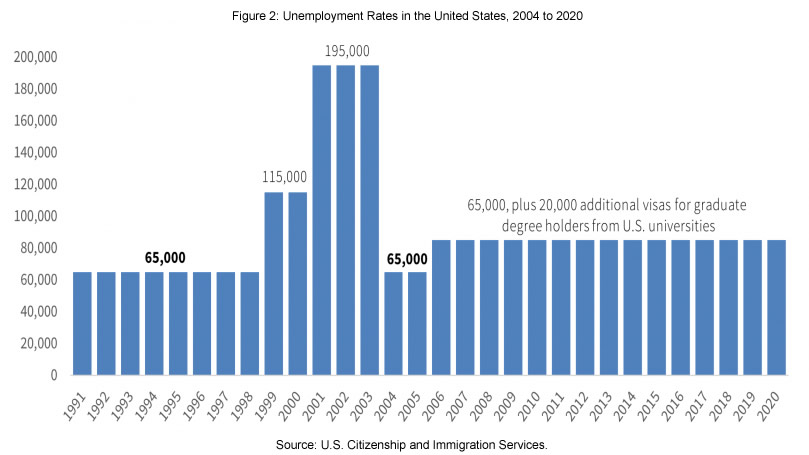

Since the category was created in 1990, Congress has limited the number of H-1Bs made available each year. The current annual statutory cap is 65,000 visas, with 20,000 additional visas for foreign professionals who graduate with a master’s degree or doctorate from a U.S. institution of higher learning (Figure 1). In recent years, the limit has been reached well before the end of the fiscal year. In Fiscal Year (FY) 2021, the cap was reached on February 16, 2021.

During the Trump administration, more H-1B petitions were initially being denied. But with a growing number of these denials being overturned, the denial rates decreased substantially during the last half of FY 2020. Denials of new H-1B petitions for initial employment rose from 6 percent in FY 2015 to a high of 24 percent in FY 2018 before dropping to 21 percent in FY 2019 and 13 percent in FY 2020. Denials of these initial employment petitions were even higher during the first half of FY 2020: 30 percent in the first quarter and 27 percent in the second quarter. However, denial rates dropped to 7 percent in the third quarter and 1.5 percent in the fourth quarter. The denial rate for petitions for continuing employment was 7 percent for FY 2020, down from 12 percent in FY 2019—but both up from just 3 percent in FY 2015. But the USCIS Administrative Appeals Office overruled Service Center denials nearly 14 percent of the time in FY 2018 and FY 2019, compared to only 3 percent of the time between FY 2014 and FY 2017. Moreover, a record number of H-1B petitioners challenged denials in federal court during the Trump administration, and a significant number have managed to get the denials reversed.

Prior to 2020, employers were required to submit full H-1B petitions without knowing whether a visa number would be available, given that demand for visa numbers usually outstrips supply. In March 2020 (for FY 2021, beginning October 1, 2020), USCIS changed to a registration process for employers that occurs before a full petition is required. The purpose of this new process was to reduce the burden on U.S. employers, and the agency, caused by requiring employers to submit complete H-1B petitions and supporting documentation prior to knowing whether a visa number would even be available. Each year, USCIS will announce the next registration period, during which a U.S. employer must register electronically for each foreign national for whom the employer intends to file an H-1B petition.

Before USCIS required registration, if the cap was hit during the first five business days, the agency conducted a lottery to determine which employers’ petitions for H-1B workers would be processed. From FY 2008 to FY 2020, the annual H-1B cap was reached within the first five business days on eight occasions.

Under the new registration process, the U.S. employer must pay a $10 fee for each registration submitted. The registration includes limited information about the U.S. employer and the foreign national, in contrast to the details USCIS requires when the U.S. employer submits a full H-1B petition. While USCIS has not placed any limit on the number of registrations a U.S. employer may file, the employer must attest that it intends to file an H-1B petition on the foreign national’s behalf and cannot submit more than one registration per foreign national.

If USCIS receives more registrations than there are visa numbers available, USCIS will run a lottery to determine who can file an H-1B petition. USCIS will select registrations for the 65,000 visa numbers first and then for the 20,000 master’s exemption visa numbers. USCIS will send notification electronically if it selects a registration. USCIS also will give the U.S. employer at least 90 days to file its H-1B petition. If those whose registrations are selected do not submit enough petitions to use the available visa numbers, USCIS has the option to make additional selections.

Foreign workers fill a critical need in the U.S. labor market—particularly in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) fields. Many opponents of the H-1B visa seek to pit native-born workers against their foreign-born colleagues. In reality, workers do not necessarily compete against each other for a fixed number of jobs.

The United States has a dynamic and powerful economy. Foreign-born workers of all types and skills, from every corner of the globe, have joined with native-born workers to build it. Skilled immigrants’ contributions to the U.S. economy help create new jobs and new opportunities for economic expansion. Indeed, H-1B workers positively impact our economy and the employment opportunities of native-born workers.

The skills that H-1B workers bring with them can be critical in responding to national emergencies. For instance, over the past decade (FY 2010-FY 2019), eight companies that were developing a coronavirus vaccine—Gilead Sciences, Moderna Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Inovio, Johnson and Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Regeneron, Vir Therapeutics, and Sanofi—received approvals for 3,310 biochemists, biophysicists, chemists, and other scientists through the H-1B program. In addition, many doctors on the front lines of the coronavirus pandemic are present on H-1B visas.

Despite suggestions to the contrary, overwhelming evidence shows that H-1B workers do not drive down wages of native-born workers, with some studies showing a positive impact on wages overall.

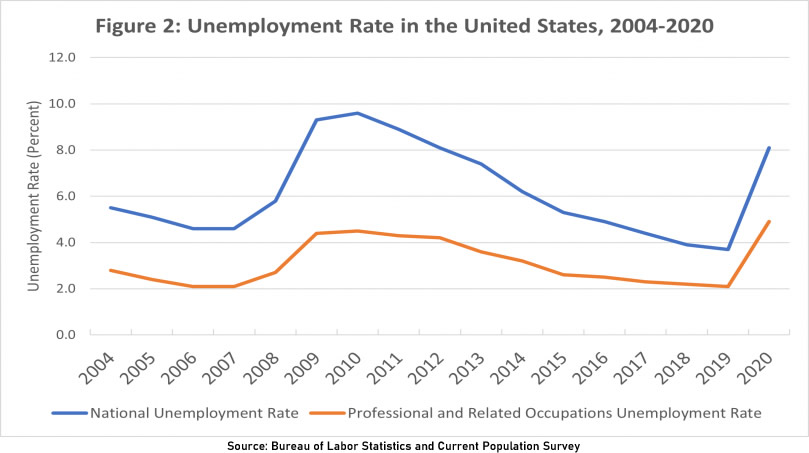

Research shows that H-1B workers complement U.S. workers, fill employment gaps in many STEM occupations, and expand job opportunities for all. The United States faces challenges in meeting the growing needs of an expanding knowledge-based innovation economy. Arguments that highly skilled, temporary foreign workers are freezing out native-born workers are rebutted by the best available empirical evidence.

Simply put, no. H-1B visas bolster innovation in the U.S. economy across America’s heartland and far beyond the technology firms in Silicon Valley. Although much research explores H-1Bs from a national perspective, there is a “geography of demand” across the United States, meaning that demand for workers in particular geographic areas often outweighs the supply of qualified workers in those areas. Moreover, although the use of H-1B visas in the high-tech industry garners substantial public attention, high-skilled immigrants play other crucial roles in the U.S. economy.